The elephant in the room

"The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt." Leviticus 19:34

"The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt." Leviticus 19:34

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

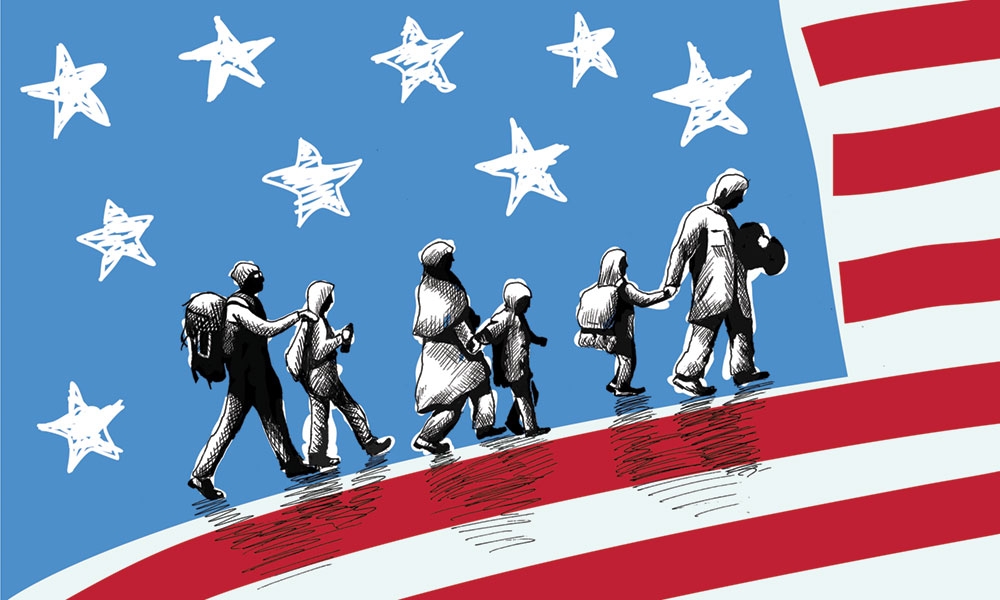

Few issues give rise to passionate arguments in our country like immigration. On the one hand, the United States of America is a large, wealthy country, often referred to as a “nation of immigrants” taking in the world’s “tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” as the 1903 inscription on the Statue of Liberty famously proclaims. On the other hand, the U.S. is a sovereign nation whose borders, laws, and culture must be protected by a government “of the people, by the people, for the people,” as Abraham Lincoln put it in the even more famous Gettysburg Address of 1863. What is a “people,” if not the citizens of a nation?

Few issues give rise to passionate arguments in our country like immigration. On the one hand, the United States of America is a large, wealthy country, often referred to as a “nation of immigrants” taking in the world’s “tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” as the 1903 inscription on the Statue of Liberty famously proclaims. On the other hand, the U.S. is a sovereign nation whose borders, laws, and culture must be protected by a government “of the people, by the people, for the people,” as Abraham Lincoln put it in the even more famous Gettysburg Address of 1863. What is a “people,” if not the citizens of a nation?

In our polarized times, many hold one of these positions absolutely and refuse to recognize the merits of the other. Do we have to choose between a Fortress America or no America at all? Thankfully, Catholic Social Teaching (CST) can help us think through this thorny yet vitally important issue. Often called the Church’s best-kept secret, CST can and should be the Church’s contribution to our discussions on immigration.

The four main principles of CST are:

- the dignity of the human person,

- the common good,

- solidarity, and

- subsidiarity.

None of these principles is meant to be used against the others in a partisan or ideological way, e.g., pitting the rights of migrants against those of citizens or higher domestic wages over moral responsibilities to the foreign poor. When considered as a whole and in a balanced way, these are not only “principles for reflection [but also] criteria for judgment [and] guidelines for action” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2423) on immigration.

It is easy to speak about principles in the abstract; it is much more difficult to apply them to actual circumstances, a skill requiring the cardinal virtue of prudence. Migrants and the countries that send and receive them differ in all sorts of ways, some of which are quite relevant for immigration policy. Politicians need to create policies that address short-term humanitarian emergencies (refugees and asylum seekers) while allowing for the reasonable inflow of immigrants, some of whom may be temporary guest workers, others future citizens. Well-off countries should not only welcome migrants to arrive in a lawful, orderly and humane manner, but also have an obligation to assist in the development of poorer countries. Social service agencies have similar duties to provide immediate basic needs such as food, clothing and shelter to all as well as eventually integrate new arrivals into society. As in so many other instances, Catholics should seek “both/and” approaches and avoid “either/or” solutions.

Pope Francis and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops have regularly and rightly drawn attention to the plight of migrants, especially from developing countries, many of whom rely on dangerous forms of human trafficking to find new homes. Destination countries with lax border controls and inefficient processing only make these problems worse by encouraging migrants to break up families and make false asylum claims. Respecting human dignity and the common good of society means emphasizing the rights and responsibilities of both migrants and host countries.

One unfortunate aspect of current debates on immigration is the inability to think beyond short-term, often economic considerations to longer-term political and social ones. Immigrants are more than just workers meant to fill the labor shortage in aging societies. Thinking of a nation as nothing more than a random collection of producers and consumers is to deny its ability to allow for the temporal and spiritual fulfillment of all. The family and nation are natural societies of this type (cf. CCC n. 1882), whose members are primarily but not exclusively responsible to others members of the same society.

On a personal note, I write as an American-born child of immigrants and later spent 20 years living in Italy. Neither experience was free of difficulties, but both were assisted by Catholics who understood the importance of welcoming this stranger and assimilating him to their way of life. I gladly learned and was personally enriched by the history, language, and culture of these countries, and hope I have been able to contribute to them as well. I also think I learned much from the example of Pope St. John Paul II, who brought me into the Church and for whom I worked in the last years of his pontificate. I’ll close with these still very much relevant words from his 1995 address to the United Nations:

“Today the problem of nationalities forms part of a new world horizon marked by a great “mobility” which has blurred the ethnic and cultural frontiers of the different peoples, as a result of a variety of processes such as migrations, mass-media and the globalization of the economy. And yet, precisely against this horizon of universality we see the powerful re-emergence of a certain ethnic and cultural consciousness, as it were an explosive need for identity and survival, a sort of counterweight to the tendency toward uniformity. This is a phenomenon which must not be underestimated or regarded as a simple left-over of the past. It demands serious interpretation, and a closer examination on the levels of anthropology, ethics and law.

This tension between the particular and the universal can be considered immanent in human beings. By virtue of sharing in the same human nature, people automatically feel that they are members of one great family, as is in fact the case. But as a result of the concrete historical conditioning of this same nature, they are necessarily bound in a more intense way to particular human groups, beginning with the family and going on to the various groups to which they belong and up to the whole of their ethnic and cultural group, which is called, not by accident, a “nation”, from the Latin word “nasci”: “to be born”. This term, enriched with another one, “patria” (fatherland/motherland), evokes the reality of the family. The human condition thus finds itself between these two poles — universality and particularity — with a vital tension between them; an inevitable tension, but singularly fruitful if they are lived in a calm and balanced way.” (Pope Saint John Paul II, Address to United Nations, 1995, Paragraph 7)

Kishore Jayabalan is the acting chair of the diocesan Commission on Catholic Social Teaching. Please visit dioceseoflansing.org/social-teaching to learn more about its work and apply for grants to promote CST in the diocese.