A Brief History of Deaconesses

During Holy Week, Pope Francis appointed Dr. Catherine Brown Tkacz to his new commission for the study of women and the diaconate. A theologian and biblical scholar of the Diocese of Spokane, she is on the external faculty of Bishop White Seminary. Her extensive scholarship on women in the Church includes several essays about the deaconesses of the past, and a forthcoming book, Deaconesses and the Sanctification of Women.

“O God, by the birth in the flesh of your Son and Our Lord Jesus Christ from a virgin, you sanctified the female, and you granted to men and to women the abiding presence of your Holy Spirit.” These words open a prayer from the rite for consecrating a woman to be a deaconess. In the early Church, deaconesses fulfilled many roles which every woman of faith could fulfill. In addition, though, the deaconess had a unique role concerning the eucharist: She took it to women who were housebound. Thus, deaconesses were the first extraordinary ministers of the eucharist, exclusively for women who could not come to church. Seeing the context in which the office of deaconess arose shows how affirmative of women the creation of deaconesses was.

Jesus emphasized the spiritual equality of the sexes as no one else had ever done. He conversed with women, healed women, responded to their intercession, and elicited from the woman Martha of Bethany the fullest profession of faith recorded in the Gospels. (Jn 11) He miraculously healed the woman with the flux of blood and praised her for her faith; he raised the daughter of Jairus from the dead. In his parables, he gave sexually balanced examples—the shepherd who finds his lost sheep, the homemaker who finds her lost coin; the servants entrusted with talents, the virgins entrusted with greeting the bridegroom.

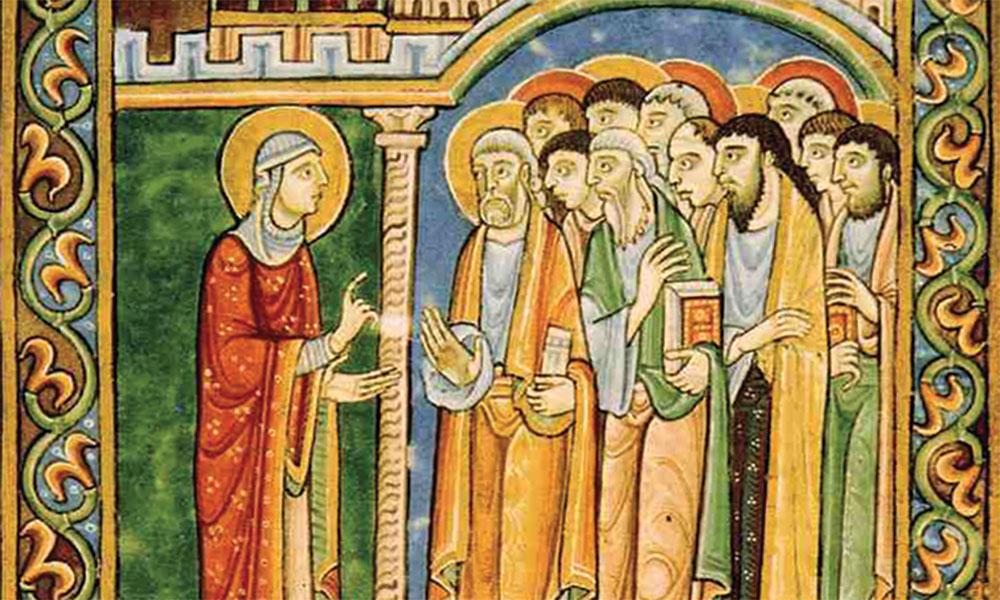

Further, God arranged that the holy commission of announcing the Resurrection to the apostles was entrusted to laywomen: Mary Magdalene and the other women at the tomb.

As a result, in the new Church, both men and women were baptized and received Communion, as attested in the Acts of the Apostles. In the Temple, women were not allowed inside but relegated to the back court. In contrast, in the new Christian churches, men and women equally came right up to the sanctuary and received the body and blood of Christ. This was revolutionary, and it deserves our marvel.

Baptism in the early Church was of adults, in the nude or in a loincloth. Soon anointings were associated with baptism, too: the eyes, lips, ears, shoulders, chest, hands, and feet were blessed with holy oil. The Church faced a pastoral problem: How to preserve the modesty of a woman being baptized and of the priest baptizing her? The solution was not to invent a “woman’s form” of baptism, a sort of “second-class” sacrament. Instead, the earliest baptismal fonts were shallow pools, often enclosed within curtains, and a woman would assist a woman being baptized with the priest pronouncing the baptismal formula. The women of faith who served in this way included relatives, widows, and deaconesses. Other services for women, such as works of practical charity, catechesis, homecare for the sick, and preparing the dead for burial, were likewise done by many women, including deaconesses.

Some work in some churches, however, was unique to deaconesses. In the East, some groups in antiquity struggled with dualism. They believed that matter is bad. Just as those groups rejected the idea of the Incarnation with its insistence that God had actually suffered on the cross, so these dualist sects such as Copts and Paulinians maintained a strong social segregation of the sexes. They would have considered it improper for a woman to speak directly to a priest or bishop, so a deaconess would accompany her. Also, some of those groups barred pregnant women from coming to church. Yet it would also have been scandalous in those regions for a priest to be seen entering a woman’s dwelling, even to bring her the Eucharist. Therefore, deaconesses were consecrated for this special service. St. John Chrysostom and others labeled such customs as barring pregnant women from church “superstitious,” and recently the Orthodox Church of America has rejected such practices as “dogmatically indefensible.” In antiquity, however, some Greek, Coptic, and Syriac churches needed deaconesses. Today, of course, a pregnant woman would not only come to church; she herself might be an extraordinary minister of holy Communion and distribute the sacrament during Mass to both men and women.

The rites for creating a deacon and a deaconess had obvious differences. Here are a few: The man to be made a deacon wore an alb; the woman to become a deaconess wore everyday attire. The man knelt on one knee; the woman stood. The bishop prayed two prayers over each, but the prayers are entirely different. The bishop handed the new deacon a rhipidion (liturgical fan), to be used during the Divine Liturgy when the deacon stood by the altar. The deaconess had no role at the liturgy and received no rhipidion. After the consecration, the bishop gave Communion to the deacon, handed him the chalice and the deacon went out of the sanctuary and gave communion to the faithful. In contrast, after the bishop gave Communion to the deaconess and handed her the chalice, she set it on the altar, for she was commissioned to give the Eucharist only to housebound women. The rites were different, because the offices were different.

By the Middle Ages, infant baptism became the norm. Sexual segregation lessened in some Eastern groups that had been dualist. Thus, the need for deaconesses waned. The fact that historically deaconesses once existed is witness to the Church’s affirmation of women. Even in those groups affected by dualism, the Church created ways to provide her daughters the sacraments of baptism and Eucharist.