The Culture Section: November 2025

This month inaugurates the new culture section of FAITH Magazine. Here, we explore how the arts, literature, movies, podcasts, music, and much more can enhance our spiritual life and draw us ever deeper in our relationship with God, through beauty, truth, goodness. We hope you enjoy these cultural offerings. Happy reading!

Sean O’Neill, editor of FAITH Magazine

This month inaugurates the new culture section of FAITH Magazine. Here, we explore how the arts, literature, movies, podcasts, music, and much more can enhance our spiritual life and draw us ever deeper in our relationship with God, through beauty, truth, goodness. We hope you enjoy these cultural offerings. Happy reading!

Sean O’Neill, editor of FAITH Magazine

Podcast

The Messy Family Podcast

One of the perennial questions asked by men and women across time and place is some form of “How should I live?” A modern version of this is the popular “life hack,” a practice or strategy that one can employ to improve one’s life. Another way of saying it is “What are the best tips and strategies to get the most out of life?

Peter Drucker, the influential writer on management theory and practice, is often quoted as saying, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Perhaps life hacks are not the answer, and we should instead be examining what kind of culture we are building in our lives and in our families.

Mike and Alicia Hernon host the “Messy Family Project” podcast as part of their larger Messy Family Project Ministry. They have been married for 25 years, have 10 children, and have a very relatable way of sharing their experience. Their style is like a big brother or sister sharing what has worked for them, rather than as an “expert” trying to declare that they’ve found the only way that works.

The title of their show obviously points to the fact that their main audience is parents raising children, but the principles they espouse when speaking of building a family culture can be applicable to anyone, with some modification.

They define a family culture as “an unwritten set of expectations that confer identity, belonging, and mission on its members.” In other words, it is the operating system or the habits of the home in which you live. It is the constant communication between members about the values and manner of how to live.

Describing their method of building a family culture briefly, it rests on five ascending pillars: the spiritual life of your home, your marriage, the system of relationships in your life, developing your God-given gifts, and daily activities that really boil down to the works of mercy.

The podcast is worth listening to as a whole, but the episodes on culture are especially helpful. You can find those topics on episodes 96, 97, 136, 218, 256, and 271.

Listen to The Messy Family Podcast here.

Music

Ave Verum Corpus

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

In 1791, Mozart wrote a small Eucharistic hymn, “Ave Verum Corpus,” that lasts about three minutes yet opens a wide door to prayer. Its power is its simplicity. The choir mostly moves together, like a single breath. Gentle “leanings” between notes melt into calm, and the musical endings rest rather than shout. Strings and organ don’t dazzle; they hold the singers like a quiet frame. Nothing competes with the One present on the altar.

This is exactly what the Church asks of sacred music. Several documents issued by the Church and former popes define the nature of sacred music. Sacrosanctum Concilium calls it a priceless treasure that belongs to the liturgy itself, because it adds joy to prayer, unites hearts, and dignifies the rites. Tra le sollecitudini says the test is holiness, true artistry, and a language people can receive — three qualities this piece embodies. Musicam sacram reminds us that participation is both outward and inward: the responses we sing and the attention we give. During Communion, a short choral piece can serve that inward attention. And De musica sacra commends reverent silence, especially after the Consecration, so that love can listen.

Pray Ave Verum as you would lectio divina; that is, read the text, prayerfully meditate silently on it, and listen once with eyes closed. Simplicity clears the way for Presence.

Television

The Wonderful World of Benjamin Cello

“The Wonderful World of Benjamin Cello” is a children’s television series that combines the highest of Christian ideals with the best of modern production values. Each episode follows the adventures of a country gentleman, Benjamin Cello, and his friends as they explore the “Land of the Baptized Imagination” through stories, songs, and art. The series is the creation of the Tennessee-based Wolaver family. The musically talented clan are relatively recent converts from evangelicalism to Catholicism.

“Our children deserve the best,” says the show’s creator, Robin Donica Wolaver, “They also deserve the truth — the truth about Jesus, the truth about God, and the truth about who they are created to be. And the best way to instill that truth is through beautiful images, great music, and fresh storytelling that inspires wonder.”

“The Wonderful World of Benjamin Cello” is available on various platforms including Formed.org. The show’s availability, and even existence, highlight one of the great blessings of the contemporary media landscape: streaming. Formerly, Catholic families felt forced to choose between the morally unpalatable table d’hôte of legacy television networks or no television at all. Now, streaming provides à la carte options for discovering and delighting in great television that upholds the good, true, and beautiful. For children, “The Wonderful World of Benjamin Cello” is a highly recommendable first pick off the menu.

Film

A Man for All Seasons

Few films can truly be called “Catholic,” and fewer still rise to the level of great cinema. “A Man for All Seasons” is one of those rare films. It not only won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1966, but also appears on the Vatican’s list of 45 films of outstanding importance.

The story follows St. Thomas More, 1478–1535, (played by Paul Scofield) during his tenure as Chancellor under King Henry VIII (Robert Shaw). The king seeks an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, so that he can wed Anne Boleyn. More is summoned before the corpulent Cardinal Wolsey (Orson Welles), who asks More to help him pressure the pope into granting the divorce. When Thomas refuses, it sparks a chain of events where Thomas finds himself caught between faith and office.

Adapted from Robert Bolt’s play, the film unfolds largely through conversations in closed rooms rather than sweeping visuals. While the cinematography and direction are good, it is the writing and performances that shine. The dialogue carries an intellectual weight rare in modern cinema, yet remains accessible for contemporary audiences. Thomas may prefer a plodding pace, but the script does not plod, moving briskly from one conflict to the next.

Contrary to what you might think, this story is not about following your conscience. The King’s own conscience compels him to seek an annulment. The difference is that Thomas understands conscience as the faculty that binds us to objective truth. As he explains to the Duke, “It is not that I believe it, but that I believe it.” His very identity is inseparable from God’s revealed truth.

When the king breaks from the Church, endangering the souls of a nation, Thomas holds his tongue. Even when he resigns his position, he gives no explanation; his silence protects his family. But when his enemies finally tear down the walls around him, More speaks openly, his stance moving from prudent silence to fearless witness.

The reckless actions of a few powerful men led generations into separation from the Church. But through this story of one steadfast saint, God has continued to strengthen and guide souls for centuries.

Orson Welles once said, “Don’t be marinated, don’t soak yourself in films.… Now of course you must see films, and you must see great films.”

We live in an age overflowing with viewing options, so we must be selective. “A Man for All Seasons” is one of those rare films truly worth watching and remembering.

- Run Time: 2 hours

- 1966, color.

- Historical Drama, Rated G. Recommended age: 12+

- Parental advisory: Some mature topics, two “G.D.” blasphemies, and an off-screen execution

Books

My Son Carlo: Carlo Acutis Through the Eyes of His Mother

by Antonia Salzano Acutis

Commentators are fond of telling young people that Carlo Acutis is relatable to them because he is just like them; a child of the digital age, a teenager confronting the challenges of modern life. This book however, which is his mother’s account of Carlo’s life, opens up for us the deeper reasons behind the Church’s decision to canonize Carlo. His mother recounts how Carlo’s unusually fervent faith and devotion first disturbed and then compelled her to become an active believer. By the age of fifteen, Carlo had pursued sanctity so doggedly that it was natural for him when given a diagnosis of aggressive leukemia to say that he wanted to offer his suffering for the Church. He is truly a heroic example of sanctity for the modern age.

Recommended for all those who work with young people.

Leo XIV — Portrait of the First American Pope

by Matthew Bunson

On May 8, 2025, something quite unexpected happened: The cardinals of the Catholic Church elected an American pope. This readable biography of Pope Leo, is an excellent introduction to his path to the papacy. Born into a Catholic family in Chicago, Illinois, Robert Francis Prevost would become first a priest of the Augustinian order, and then a leader both of that order and of the missionary peoples he would serve. This book documents how he would be then called to serve the wider Church in Rome first as a cardinal and then as its pontiff. His first sermon after being elected is included in this volume.

Recommended for new Catholics interested in Pope Leo’s life and White Sox fans!

A Daily Defense: 365 days (Plus One) to Becoming a Better Apologist

by Jimmy Akin

Jimmy Akin, Catholic convert and popular apologist offers readers 365 (plus one) days of succinct ways to respond to the most common modern challenges to faith. On subjects ranging from the existence of God to the theology of purgatory, Akin lays out the substance of each objection and then suggests a solid path to pursue a counterargument. Whether you wish to understand and answer your own doubts about faith or seek to engage others in the conversation, this book is an impressively referenced and thoughtful resource.

Recommended for apologists, evangelists, and as a gift for intellectually curious teenagers and students.

Art

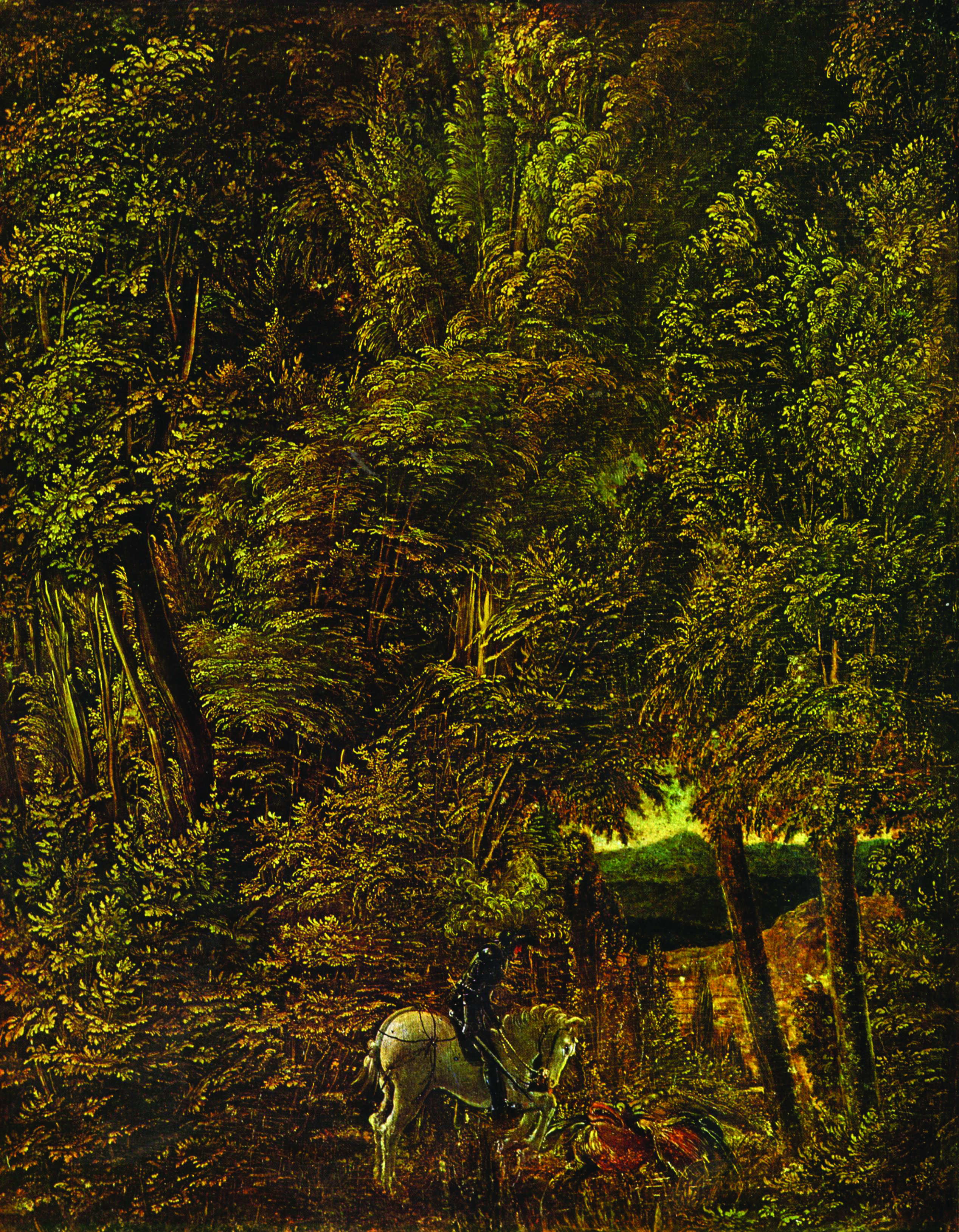

Saint George in the Forest

Albrecht Altdorfer, 1480-1538

Albrecht Altdorfer’s St. George in the Forest may not strike many viewers as an overtly sacred piece of art. Painted in oil on parchment and mounted on linden, the work is the size of a piece of printer paper. The saint himself lacks the drama of many depictions of this legendary battle, while the dragon is so successfully camouflaged that one hardly takes notice of it.

Altdorfer was a German painter, engraver, and architect during the Renaissance, and while his work often displays the era’s Christian content and stylistic influences, a passion for landscape sets his work apart. A leader of the Danube school, he pioneered landscape as an independent genre, but in many works, as here, he blends his attention to the natural world with a religious theme.

Natural wonder lends itself to awe of the Creator; in such an economy of scale, even the saints are small. The almost overwhelming density of the vegetation pairs with the vague threat of the dragon, a familiar theme to Christians who are aware that spiritual battle can be multi-faceted, protracted, and even unnoticed. Saint George appears unafraid but not self-reliant: Altdorfer seems to say that the power to defeat the dragon comes from something much greater. In the distant view of the horizon, the artist confirms there is a way through the forest — and to victory.